Monsignor Juan José Gerardi Conedera

- Profiles in Catholicism

- May 12, 2018

- 8 min read

Updated: Feb 21, 2019

by Judith Berry

A Death in Guatemala (Monsignor Juan José Gerardi Conedera) An Interview with Daniel Hernandez-Salazar by Judith Barry

Reprinted with Permission from the November, 1998

Journal of The International Association of Physicians in AIDS Care

The 36-year civil war in Guatemala officially ended with the election in January 1996, of President Alvaro Arzú Irigoyen. The subsequent peace accord between the government and the leftist guerrillas has led to a reduction in reporting of human rights violations. However, Guatemala still has the second highest per-capita crime rate in Latin America, second only to Columbia. The January 1998 terrorist attack on a busload of St. Mary's College students and faculty underscores the degree to which civil rights and safety are still in jeopardy in Guatemala.

This violence has its roots in 1954 when President Dwight D. Eisenhower authorized the CIA to overthrow the lawfully elected government of Jacobo Arbenz at the behest of the United Fruit Company, now known as Chiquita-Brands International. Recently, the well-publicized case of Jennifer Harbury, a Harvard-trained lawyer and US citizen married to a Guatemalan commando, has focused public attention on the long-term nature of the CIA's involvement. When her husband, Efraín Bámaca, "disappeared" after being wounded in combat, the Guatemalan military maintained that he had died immediately, but later US Senator Robert Torricelli (D.-NJ) confirmed publicly that Bámaca had been taken into custody by the Guatemalan army, tortured and finally extrajudicially executed. High-ranking CIA officials were intimately acquainted with the circumstances of Bámaca's death although their culpability was never proved. However, the global publicity surrounding this case led President Bill Clinton to order an official inquiry into these and other cases involving US citizens in Guatemala. Ultimately, several CIA employees were disciplined and two were dismissed.

One of the many difficulties Harbury faced in trying to ascertain what had happened to her husband was discovering in which of the many clandestine and unmarked mass graves he was buried. With the end of the war the discovery of these sites led to the necessary process of exhuming and identifying the bodies. A number of people volunteered to help including Daniel Hernandez, a Guatemalan artist and former photojournalist for Reuters and the Associated Press. During this period Hernandez produced the remarkable images, popularly known as the "angel" series, which have become the symbols of human rights in Guatemala.

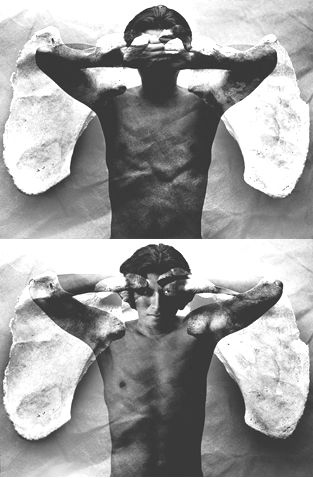

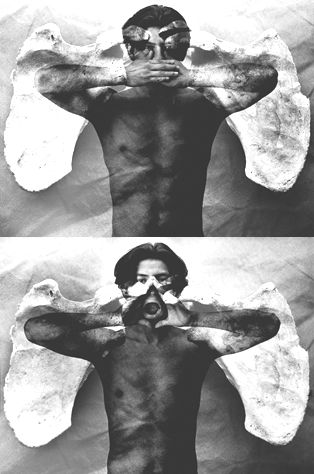

As Hernandez was working in the graves, he became fascinated with the beauty and poetic quality of some of the human bones. In particular, the scapulae reminded him of angel wings. He first combined them with male figures who covered their eyes, ears, and mouth with their hands, symbolizing the self-imposed blindness, deafness, and silence of the Guatemalan people to the murder of thousands of "enemies" of the Guatemalan military during the three-and-a-half decade war of counterinsurgency.

These images came to the attention of the Catholic Archbishop's office in Guatemala which commissioned a fourth "angel" with its mouth open to symbolize the responsibility to speak the truth--the truth recorded in the Project for the Recovery of Historic Memory. The "angel" pictures are the cover art for this four-part document detailing over 37,000 human rights violations, most of which were at the behest of the Guatemalan army.

Two days after the public presentation of this report in the Cathedral of Guatemala City on April 24, 1998, the bishop who commissioned the study, Monsignor Juan Gerardi, was bludgeoned to death with an eight-pound block of cement. The bishop's skull was crushed. His brains were splattered on the floor of his garage. His face was so disfigured that he could only be identified by a ring on his finger. Forty-eight hours later thousands of Guatemalan citizens marched in a silent protest, carrying placards adorned with large blow-ups of Hernandez's "angel" photos.

Subsequently, these images have been widely exhibited on television, in newspapers, on Web sites devoted to Guatemala, and in art galleries such as the Aldo Castillo Gallery in Chicago and the Primary Object Gallery in San Antonio, Texas. The following interview took place in September 1998.

Journal: What led you to volunteer to work in the mass graves?

Hernandez: I have always been interested in facing challenges in my life and making other people do the same. Exposure to the social and psychological effects of this civil war made me find a way to represent what I felt. I also believed that it was very important to make people aware of what happened during those years. The testimony of those terrible things are the remains of the victims buried in the clandestine graves, so I decided to include them in my art.

When I worked as a photojournalist, my objective was to produce truthful images reflecting the living conditions of this country. Now, working as an artist, I want to produce powerful images to make people here understand the importance of exhuming our recent past. Simultaneously, I want to get the rest of the world involved in what happened here.

When I worked with news agencies I had the chance to take photos of the exhumations, but I always wished for more time so that I could make a personal interpretation of what I saw. Press agencies are always rushing to be first with pictures. Now that I am working for myself, I am able to invest as much time as I need to produce the images. More than helping to identify the remains of the victims, I want to call public attention to what has happened--to use the power of these images to emphasize that this must never happen again. It is similar to the message a visitor receives at the US Holocaust Museum.

Journal: Who are in these graves?

Hernandez: The people buried in the graves are ordinary people: peasants in the countryside, students, union workers, and human rights activists from the cities, all of whom were actively struggling for their rights. Additionally, there are other victims who happened to be in the wrong place at the wrong time.

Journal: What in particular led you to conceive the "angel" series?

Hernandez: The idea for the "angel" series came to me in July 1997 after the exhumation of nine peasants in a grave on a remote farm. The peasants were murdered by the Guatemalan army after protesting that their salaries had not been paid for two years. The "angel" series is part of a larger series, "Eros+Thanatos," where I combined images of male nudes with human remains to represent my thoughts about life and death. I wanted to show how the Guatemalan people do not want to face their problems, especially the violence and massacres that happened during the armed conflict. I also wanted to show the impossibility of free expression.

I proposed the fourth "angel" with its mouth open to the director of the archbishop's human rights office after they decided to use the "angel" series to illustrate the four-volume report of the Project for the Recovery of Historic Memory (Proyecto Interdiocesano de Recuperación de la Memoria Historica/acronym REMHI). With the addition of the fourth "angel" to the three earlier ones, I made a new piece "Esclarecimiento" which became the poster for the presentation of the REMHI report on April 24, 1998.

Journal: What have been the reactions to the images?

Hernandez: Strong. I remember the comment of a secretary when she saw the fourth (speaking) "angel." The image was printed on the invitation card for the presentation ceremony at the Cathedral in Guatemala City. She said, "It is beautiful...but it scares me." And a woman at the Aldo Castillo Gallery in Chicago told me that the pictures expressed the feelings of a close friend who left Guatemala because of death threats.

Journal: What is the Project for the Recovery of Historic Memory?

From the series of Angels -- No oigo, No veo, Me callo, Nunca mas." Daniel Hernandez © 1997

Hernandez: The project was conceived by Monsignor Juan Gerardi who directed the project until the presentation of the report and his assassination two days later. His team of sociologists, psychologists, historians and lawyers, working with the Catholic Church in every region of Guatemala, collected thousands of testimonies given by victims of the war, their relatives, and members of the security forces--the army, paramilitary groups, and death squads--describing crimes committed during the war. This team classified and analyzed all the information to produce the four-book report, "Guatemala, Never Again." The first book is about the effects of violence (cover image: angel covering his eyes); the second book (cover image: angel covering his mouth) describes the structure of the repressive forces and the torture techniques that were used; the third book (cover image: angel covering his ears) discusses the historic events that provoked the war; and the fourth book (cover image: angel with his mouth open, speaking) contains the names of more than 20,000 victims who died during the war.

Journal: What was the reaction of the Guatemalan army to the report, especially since they are charged with the majority of the 37,000 human rights abuses recounted in it?

Hernandez: The first reaction was silence. After that, they tried to minimize the information written in the report. Colonel Noak, an army officer (the army's former spokesman) who was interviewed by the short-wave radio station Radio Netherlands two-and-a-half months ago, said the army should ask forgiveness from the people for the "excesses" it committed during the war. Shortly after his interview was broadcast, he was captured and imprisoned. The reason the army gave for his arrest was that he spoke without permission. One month later, he was released. This shows how the army, as in other instances here, doesn't want to face what it did.

Journal: Was there a relationship between the unveiling of the report and Monsignor Gerardi's assassination?

Hernandez: Nothing has been proved, but the Catholic Church, human rights groups, and many people believe he was killed because of the report. There is very little hope that the actual murderer(s) and the intellectual murderer(s) behind the assassination will be captured. Recently Father Orantes, Gerardi's assistant at his parish church, was arrested and charged with the murder. Monsignor Gerardi's corpse will be exhumed so it can be re-examined. There is a lot of confusion. People who do not like the report want it to be forgotten. But the report is circulating widely. The first edition of 2,500 copies sold out. There will be another edition of 5,000 by the end of this year. Plus 150,000 copies were published in newspaper format and distributed free. There are offers to do editions in other languages. I think the bishop's murder was politically motivated and all this contradictory information (disinformation) is intended to confuse public opinion, dilute the report's impact, and make it more difficult to resolve the crime.

Journal: How did the silent protest after the assassination come about?

Hernandez: I think it was organized by the Catholic Church and various human rights organizations. The Archbishop's human rights office initially printed posters with the "angel" photos to announce the presentation ceremony at the Cathedral. Since the Church still had some posters when Monsignor Gerardi was killed, they distributed them so that people could use them as placards in the protest march. And some people who had already received the posters brought them as well.

Journal: What do you see as the most effective site for your images--television, newspapers, the Gerardi Web site?

Hernandez: If I think "effective" depends on how many people saw the images and got the message, I would say the poster was the most effective medium because it was everywhere. Also the newspapers, because the images appeared there so frequently. But if I understand "effective" as the place where the images were best presented and observed, I would say the galleries here and abroad.

Journal: What has been the most effective medium for reaching people in Guatemala?

Hernandez: I think the poster because the people really liked it. Many of the posters hanging in churches and universities were taken by people who wanted to have one. People framed them and hung them in their homes and businesses. I was very sad when the bishop was killed, but at the same time I was proud to see my work in the hands of so many people who found it representative of what they wanted to say in that moment during the march. In some way they "appropriated" the images as their own. I can compare my sensation to that of a composer when he hears one of his compositions sung by hundreds of people because they like and identify with it.

All photographs © are property of Daniel Hernandez

Judith Barry is an artist and writer who lives in New York.